|

| Ace and I watch Tori fly a kite at the beach. |

A friend and I texted and tweeted back and forth about it while I rocked the baby to sleep and kept an eye on the two older boys. Of course I was worried; Julian was out with friends and I sent him a text warning him to be particularly careful in case the police were extra jumpy. Certainly what is happening in Ferguson is big. It just isn't...news. It isn't news to anyone who loves a black boy and has journeyed with him through the world. So here is my response to the pleas from Christians who are asking me via Twitter to be outraged, to be vocal, to be active:

I am tired of outrage. I am tired of despair. I am tired of talking about race to white people who tell me I am suffering from white guilt or have imagined it or don't I know the Lord is color-blind and my goodness, I don't even *see* race myself.

|

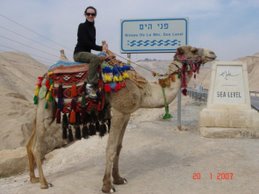

| I am tired of wondering when people will stop thinking this face is charming and start seeing it as menacing. |

There are a million things I could say about Ferguson, all of which have been said by people who are more eloquent and more vocal than I am. I could point out that if you'd been paying attention, you'd have known about the slaying of Mike Brown almost a week ago. I could say that the police are no more racist than the rest of us, but that this action shouldn't come as a surprise when you give them military-grade weapons with which to act out those prejudices. I could say that the police have been brutalizing black people for decades, they just didn't have such fancy riot gear. I could say that if you think this isn't America, you live in a bubble; this has always been America. I could point out the way black victims are often identified by any misconduct and white perpetrators are often treated as people with great potential who went tragically wrong. I could say that the way we defend Mike Brown by saying things like "he was going to college" as if that made him more valuable, like he deserved to be shot a little less, demonstrates how much we've dehumanized black people: we have to defend their right to exist. I could say I'm worried that this will be another cycle of social media outrage that fizzles when we find something else to fixate on. I could say that all the venting and retweeting and favoriting may make us feel like we're doing something in lieu of actually, you know, DOING something.

I could speak to you of quieter things, too: of teenage boys who are raucous and goofy because that's what teenage boys are like, and the fear that a police officer--or, hell, any citizen with a gun and some fear--won't wait to find out that Phen is great at math and Julian is a brilliant musician, that Phen is reading The Art of War and Julian believes his patronus would be a panther if he ever gets his Hogwarts letter. I could tell you I don't just worry about the boys; I worry about my friend Corregan, he of the Princeton degree and megawatt grin, who is cerebral and compassionate and wildly funny and who, at 6-4 and 200+ pounds, is someone's idea of the bogeyman, and I worry about my friend Runako, who by his own admission "gets stroppy" when his rights are being trampled on, and I worry about my friend Mijha, who refused to watch any news coverage of this because she is tired of caring too much. I could tell you that my pastor--my soft-spoken, gentle-spirited pastor--is the one who taught Phen how to behave when approached by police, how to narrate every movement ("My license is in my wallet, which is in my pocket, so I'm going to reach for it now if that's OK") and be as unthreatening as possible. I could tell you that it's tempting to tell the boys to avoid any protests or demonstrations in hopes of keeping them safe and the gut-wrenching realization that I'd be trading their physical safety for their dignity and self-respect. What kind of person would I be to ask that of them? What kind of young men would they be if they made that trade? I could tell you that 17 years into this life I've chosen, of living and working and worshipping across racial lines, I've learned that the resilience of black people is awe-inspiring, because everything conspires to try to make them smaller and meaner than they were meant to be. I could tell you I'm up at 1 am writing this blog post because Julian isn't home yet, which is fine--he's 19 and it's summer--but I worry until I hear his key in the lock.

So I am tired, because this is not an event, this is just life. And I am embarrassed to admit I am tired because black people do this every day with no choice and no complaint. I could, if I wanted to, walk away from all this. (Well, in theory; in reality, I'd only have about five friends left and I'd have to find a new church, new apartment and new life.) The privilege of being white is that I can choose not to think about race; I can choose not to care. Even if I don't make that choice, it's there; I have options.

Even typing that sentence is laborious because I've said it so many times. This is where I hit the wall. There is a zeal to some in the New Evangelical movement that I admire. I am so pleased that being an evangelical and caring about social justice are no longer mutually exclusive. I am thrilled that we are no longer a wholly owned subsidiary of the Republican Party. I am so glad that there are speakers and blogger and pastors and thinkers who are talking about race and injustice, and they are passionate and zealous and I thank God for them.

But I remember when I was the only one in the room, and I remember when Sojourners was a struggling little outfit that had about 30 subscribers and could barely pay their rent, and being a white Christian who grappled with racial injustice was lonely. I'm a little suspicious of your zeal; I'm afraid it won't last. And if I'm honest, I'm not just tired. I'm angry. I'm angry that so many of you found out about racism yesterday--or six months ago, or a year ago, or five years ago. And I know it's irrational because someone could just as easily say it of me: what's 17 years to someone who's been doing it for 30 or 40? Who lives it in their skin every day? I know that the same questions I roll my eyes at are questions I once asked, and people were kind enough to answer them without any visible eye-rolling. That's how I learned. I owe you that, and I'm failing you.

And I'm failing you if I don't tell you that as exhausting and draining and deeply, deeply sad as this work can be, it is where the Kingdom grows and where God is at work; it is vibrant and meaningful and joyous as well. Fifteen years ago, I landed at City of Refuge Church. That I found it at all is what my charismatic friends would call a "divine appointment." At the time, it had maybe 60 people. It didn't have a building; it met in a room at a homeless shelter in Houston's historically black Third Ward neighborhood. But I had interned at that homeless shelter a few years earlier, and the pastor had been the spiritual life director there. And this little church, which drew a motley congregation which included the former district attorney of Houston and several former inmates whom he had probably prosecuted, had a bold vision of being a glimpse of the Kingdom of God, a place where believers reached across lines of race and class, where there was enough for everyone and no one went without. It felt like the home I hadn't known I was looking for. And while I didn't grow up there, over the next 10 years that church grew me up spiritually.

We didn't always know exactly what we were doing. No one in multiracial churches does. That is one of the first things that people who study multiracial churches will tell you: they are too new and too few for anyone to know what makes them work or, more often, not work. They are an unknown quantity, this wild adventurous leap of faith that dares to imagine that the way things are is not the way they have to be. We hit all the bumps in the road: the people who left the church because the reality of interracial fellowship was so much harder than the dream; disputes over who would fill leadership roles; conflict over leadership styles and musical styles. It has not been easy. We've all been angry and we've all cried.

But it's where I first experienced palpable grace in for the form of black folks who took a chance on me and loved me when they had no reason to. It's where people extended their trust and I did my best to hold that fragile, precious thing and not break it--and when I did, they offered it again. It's where I learned to listen. It's where I found out that recovering addicts are the wisest people in the world and if you're smart, you'll befriend some, and they'll take care of you when you discover your own brokenness. It's where I sat in a huddle with people ranging from a partner in one of the city's biggest law firms to a woman who lived at the homeless shelter and read Bonhoeffer's "Life Together" as we tried to figure out how to live into the Beloved Community.

I'm tired and angry. I'm also joyous and exhilarated. I'm angry with you for not coming to the table sooner. Today I told Mijha "I know I should be glad they're coming to the party, even if they're late" and Mijha said, "Late?! The plates have been cleared and we're having coffee! We're putting on our coats! Don't bother to show up now!"

I feel mean and hypocritical for feeling that way, but there it is. You're late and I'm angry; I went to a lot of funerals while you were off not knowing that racism and all its attendant evils were killing a lot of the people I loved. I pray to be gracious; I usually fail. Please be patient with me as I try to be patient with you. I'll answer your questions and I'll recommend books and I'll tell my stories; as best I can, I'll point you toward Jesus, who seems to like to hang out with the oppressed and marginalized. I'll assure you that my neighborhood isn't scary, that I prefer it to tonier areas because the parties are better and the people are kinder. I'll remember Fannie Lou Hamer saying the Kingdom of God was like a banquet table, a Sunday-dinner-on-the-grounds, and that there was enough for everyone and everyone was invited, even James Eastland and Ross Barnett, "but they'll have to learn some manners." I'll remind you to bring your manners and your appetite because there's enough for everyone at the welcome table and no one need go without, and I'll celebrate when you show up.

But sometimes I'll wish you'd come sooner. Sometimes I'll resent the way you dominate the conversation. Sometimes I'll roll my eyes at your enthusiasm. I'll know you haven't gotten knocked down yet. I'll worry you won't have the stamina for it and you'll disappear. I'll worry that you'll hurt people who really shouldn't have to take any more pain.

Remind me, when that happens, that I am not vice-Jesus and God is the host of the banquet, not me.

So come join us, but stick around when the attention has moved on from Ferguson. Be prepared for your whole life to feel like Ferguson sometimes. Be prepared for big pain and bigger love.

Julian's home.

|

| Phen's graduation, June 2014. |